Banach–Tarski paradox

The Banach–Tarski paradox is a theorem in set theoretic geometry which states that a solid ball in 3-dimensional space can be split into a finite number of non-overlapping pieces, which can then be put back together in a different way to yield two identical copies of the original ball. The reassembly process involves only moving the pieces around and rotating them, without changing their shape. However, the pieces themselves are complicated: they are not usual solids but infinite scatterings of points. A stronger form of the theorem implies that given any two "reasonable" objects (such as a small ball and a huge ball), either one can be reassembled into the other. This is often stated colloquially as "a pea can be chopped up and reassembled into the Sun".

The reason the Banach–Tarski theorem is called a paradox is because it contradicts basic geometric intuition. "Doubling the ball" by dividing it into parts and moving them around by rotations and translations, without any stretching, bending, or adding new points, seems to be impossible, since all these operations preserve the volume, but the volume is doubled in the end.

Unlike most theorems in geometry, this result depends in a critical way on the axiom of choice in set theory. This axiom allows for the construction of nonmeasurable sets, collections of points that do not have a volume in the ordinary sense and require an uncountably infinite number of arbitrary choices to specify. Robert Solovay showed that the axiom of choice, or a weaker variant of it, is necessary for the construction of nonmeasurable sets by constructing a model of ZF set theory (without choice) in which every geometric subset has a well-defined Lebesgue measure. On the other hand, Solovay's construction relies on the assumption that an inaccessible cardinal exists (which itself cannot be proven from ZF set theory); Saharon Shelah later showed that this assumption is necessary.

The existence of nonmeasurable sets, such as those in the Banach–Tarski paradox, has been used as an argument against the axiom of choice. Nevertheless, most mathematicians are willing to tolerate the existence of nonmeasurable sets, given that the axiom of choice has many other mathematically useful consequences.[1]

It was shown in 2005 that the pieces in the decomposition can be chosen in such a way that they can be moved continuously into place without running into one another.[2]

Contents |

Banach and Tarski publication

In a paper published in 1924,[3] Stefan Banach and Alfred Tarski gave a construction of such a "paradoxical decomposition", based on earlier work by Giuseppe Vitali concerning the unit interval and on the paradoxical decompositions of the sphere by Felix Hausdorff, and discussed a number of related questions concerning decompositions of subsets of Euclidean spaces in various dimensions. They proved the following more general statement, the strong form of the Banach–Tarski paradox:

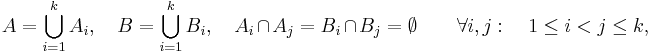

- Given any two bounded subsets A and B of a Euclidean space in at least three dimensions, both of which have a non-empty interior, there are partitions of A and B into a finite number of disjoint subsets, A = A1 ∪ ... ∪ Ak, B = B1 ∪ ... ∪ Bk, such that for each i between 1 and k, the sets Ai and Bi are congruent.

Now let A be the original ball and B be the union of two translated copies of the original ball. Then the proposition means that you can divide the original ball A into a certain number of pieces and then rotate and translate these pieces in such a way that the result is the whole set B, which contains two copies of A.

The strong form of the Banach–Tarski paradox is false in dimensions one and two, but Banach and Tarski showed that an analogous statement remains true if countably many subsets are allowed. The difference between the dimensions 1 and 2 on the one hand, and three and higher, on the other hand, is due to the richer structure of the group Gn of the Euclidean motions in the higher dimensions, which is solvable for n =1, 2 and contains a free group with two generators for n ≥ 3. John von Neumann studied the properties of the group of equivalences that make a paradoxical decomposition possible, identifying the class of amenable groups, for which no paradoxical decompositions exist. He also found a form of the paradox in the plane which uses area-preserving affine transformations in place of the usual congruences.

Formal treatment

The Banach–Tarski paradox states that a ball in the ordinary Euclidean space can be doubled using only the operations of partitioning into subsets, replacing a set with a congruent set, and reassembly. Its mathematical structure is greatly elucidated by emphasizing the role played by the group of Euclidean motions and introducing the notions of equidecomposable sets and paradoxical set. Suppose that G is a group acting on a set X. In the most important special case, X is an n-dimensional Euclidean space, and G consists of all isometries of X, i.e. the transformations of X into itself that preserve the distances. Two geometric figures that can be transformed into each other are called congruent, and this terminology will be extended to the general G-action. Two subsets A and B of X are called G-equidecomposable, or equidecomposable with respect to G, if A and B can be partitioned into the same finite number of respectively G-congruent pieces. It is easy to see that this defines an equivalence relation among all subsets of X. Formally, if

and there are elements g1,...,gk of G such that for each i between 1 and k, gi (Ai ) = Bi , then we will say that A and B are G-equidecomposable using k pieces. If a set E has two disjoint subsets A and B such that A and E, as well as B and E, are G-equidecomposable then E is called paradoxical.

Using this terminology, the Banach–Tarski paradox can be reformulated as follows:

- A three-dimensional Euclidean ball is equidecomposable with two copies of itself.

In fact, a sharp result (due to Raphael M. Robinson) is known in this case: doubling the ball can be accomplished with five pieces; and fewer than five pieces will not suffice.

The strong version of the paradox claims:

- Any two bounded subsets of 3-dimensional Euclidean space with non-empty interiors are equidecomposable.

While apparently more general, this statement is derived in a simple way from the doubling of a ball by using a generalization of Bernstein–Schroeder theorem due to Banach that implies that if A is equidecomposable with a subset of B and B is equidecomposable with a subset of A, then A and B are equidecomposable.

The Banach–Tarski paradox can be put in context by pointing out that for two sets in the strong form of the paradox, there is always a bijective function that can map the points in one shape into the other in a one-to-one fashion. In the language of Georg Cantor's set theory, these two sets have equal cardinality. Thus, if one enlarges the group to allow arbitrary bijections of X then all sets with non-empty interior become congruent. Likewise, we can make one ball into a larger or smaller ball by stretching, in other words, by applying similarity transformations. Hence if the group G is large enough, we may find G-equidecomposable sets whose "size" varies. Moreover, since a countable set can be made into two copies of itself, one might expect that somehow, using countably many pieces could do the trick. On the other hand, in the Banach–Tarski paradox the number of pieces is finite and the allowed equivalences are Euclidean congruences, which preserve the volumes. Yet, somehow, they end up doubling the volume of the ball! While this is certainly surprising, some of the pieces used in the paradoxical decomposition are non-measurable sets, so the notion of volume (more precisely, Lebesgue measure) is not defined for them, and the partitioning cannot be accomplished in a practical way. In fact, the Banach–Tarski paradox demonstrates that it is impossible to find a finitely-additive measure (or a Banach measure) defined on all subsets of a Euclidean space of three (and greater) dimensions that is invariant with respect to Euclidean motions and takes the value one on a unit cube. In his later work, Tarski showed that, conversely, non-existence of paradoxical decompositions of this type implies the existence of a finitely-additive invariant measure.

The heart of the proof of the "doubling the ball" form of the paradox presented below is the remarkable fact that by a Euclidean isometry (and renaming of elements), one can divide a certain set (essentially, the surface of a unit sphere) into four parts, then rotate one of them to become itself plus two of the other parts. This follows rather easily from a F2-paradoxical decomposition of F2, the free group with two generators. Banach and Tarski's proof relied on an analogous fact discovered by Hausdorff some years earlier: the surface of a unit sphere in space is a disjoint union of three sets B, C, D and a countable set E such that, on the one hand, B, C, D are pairwise congruent, and, on the other hand, B is congruent with the union of C and D. This is often called the Hausdorff paradox. By carefully analyzing the structure of this argument, Raphael M. Robinson proved in 1947 that the minimal number of pieces in a paradoxical decomposition of the ball is five, completely answering a question put forth by von Neumann in 1929.

Connection with earlier work and the role of the axiom of choice

Banach and Tarski explicitly acknowledge Giuseppe Vitali's 1905 construction of the set bearing his name, Hausdorff's paradox (1914), and an earlier (1923) paper of Banach as the precursors to their work. Vitali's and Hausdorff's constructions depend on Zermelo's axiom of choice ("AC"), which is also crucial to the Banach–Tarski paper, both for proving their paradox and for the proof of another result:

- Two Euclidean polygons, one of which strictly contains the other, are not equidecomposable.

They remark:

- Le rôle que joue cet axiome dans nos raisonnements nous semble mériter l'attention

- (The role this axiom plays in our reasoning seems to us to deserve attention)

and point out that while the second result fully agrees with our geometric intuition, its proof uses AC in even more substantial way than the proof of the paradox. Thus Banach and Tarski imply that AC should not be rejected simply because it produces a paradoxical decomposition. Indeed, such an argument would also reject some geometrically intuitive statements!

However, in 1949 A.P. Morse showed that the statement about Euclidean polygons can be proved in ZF set theory and thus does not require the axiom of choice. In 1964, Paul Cohen proved the equiconsistency of the axiom of choice with the rest of set theory, which implies that ZFC (ZF set theory with the axiom of choice) is consistent if and only if ZF theory without choice is consistent. Using Cohen's technique of forcing, Robert M. Solovay later established, under the assumption that the existence of an inaccessible cardinal is consistent, that in the absence of choice it is consistent to be able to assign a Lebesgue measure to any subset in Rn, contradicting the Banach–Tarski paradox (BT). Solovay's results extend to ZF supplemented by a weak form of AC called the axiom of dependent choice, DC. It follows that

- Banach–Tarski paradox is not a theorem of ZF, nor of ZF+DC (Wagon, Corollary 13.3).

Most mathematicians presently accept AC. As Stan Wagon points out at the end of his monograph, the Banach–Tarski paradox is more significant for its role in pure mathematics than it is to foundational questions. As far as the axiom of choice is concerned, BT plays the same role as the existence of non-measurable sets. But the Banach–Tarski paradox is more significant for the rest of mathematics because it motivated a fruitful new direction for research, amenability of groups, which has nothing to do with the foundational questions.

In 1991, using then-recent results by Matthew Foreman and Friedrich Wehrung,[4] Janusz Pawlikowski proved that the Banach–Tarski paradox follows from ZF plus the Hahn–Banach theorem.[5] The Hahn–Banach theorem doesn't rely on the full axiom of choice but can be proved using a weaker version of AC called the ultrafilter lemma. So Pawlikowski proved that the set theory needed to prove the Banach-Tarski paradox, while stronger than ZF, is weaker than full ZFC.

A sketch of the proof

Here we sketch a proof which is similar but not identical to that given by Banach and Tarski. Essentially, the paradoxical decomposition of the ball is achieved in four steps:

- Find a paradoxical decomposition of the free group in two generators.

- Find a group of rotations in 3-d space isomorphic to the free group in two generators.

- Use the paradoxical decomposition of that group and the axiom of choice to produce a paradoxical decomposition of the hollow unit sphere.

- Extend this decomposition of the sphere to a decomposition of the solid unit ball.

We now discuss each of these steps in more detail.

Step 1. The free group with two generators a and b consists of all finite strings that can be formed from the four symbols a, a−1, b and b−1 such that no a appears directly next to an a−1 and no b appears directly next to a b−1. Two such strings can be concatenated and converted into a string of this type by repeatedly replacing the "forbidden" substrings with the empty string. For instance: abab−1a−1 concatenated with abab−1a yields abab−1a−1abab−1a, which contains the substring a−1a, and so gets reduced to abaab−1a. One can check that the set of those strings with this operation forms a group with neutral element the empty string e. We will call this group F2.

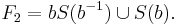

The group  can be "paradoxically decomposed" as follows: let S(a) be the set of all strings that start with a and define S(a−1), S(b) and S(b−1) similarly. Clearly,

can be "paradoxically decomposed" as follows: let S(a) be the set of all strings that start with a and define S(a−1), S(b) and S(b−1) similarly. Clearly,

but also

and

The notation aS(a−1) means take all the strings in S(a−1) and concatenate them on the left with a.

Make sure that you understand this last line, because it is at the core of the proof. Now look at this: we cut our group F2 into four pieces (actually, we need to put e and all strings of the form an into S(a−1)), then "shift" two of them by multiplying with a or b, then "reassemble" two pieces to make one copy of  and the other two to make another copy of

and the other two to make another copy of  . That's exactly what we want to do to the ball.

. That's exactly what we want to do to the ball.

Step 2. In order to find a group of rotations of 3D space that behaves just like (or "isomorphic to") the group  , we take two orthogonal axes, e.g. the x and z axes, and let A be a rotation of arccos(1/3) about the first, x axis, and B be a rotation of arccos(1/3) about the second, z axis (there are many other suitable pairs of irrational multiples of π, that could be used here instead of arccos(1/3) and arccos(1/3), as well). It is somewhat messy but not too difficult to show that these two rotations behave just like the elements a and b in our group

, we take two orthogonal axes, e.g. the x and z axes, and let A be a rotation of arccos(1/3) about the first, x axis, and B be a rotation of arccos(1/3) about the second, z axis (there are many other suitable pairs of irrational multiples of π, that could be used here instead of arccos(1/3) and arccos(1/3), as well). It is somewhat messy but not too difficult to show that these two rotations behave just like the elements a and b in our group  . We'll skip it, leaving the exercise to the reader. The new group of rotations generated by A and B will be called H. We now also have a paradoxical decomposition of H. (This step cannot be performed in two dimensions since it involves rotations in three dimensions. If we take two rotations about the same axis, the resulting group is commutative and doesn't have the property required in step 1.)

. We'll skip it, leaving the exercise to the reader. The new group of rotations generated by A and B will be called H. We now also have a paradoxical decomposition of H. (This step cannot be performed in two dimensions since it involves rotations in three dimensions. If we take two rotations about the same axis, the resulting group is commutative and doesn't have the property required in step 1.)

Step 3. The unit sphere S2 is partitioned into orbits by the action of our group H: two points belong to the same orbit if and only if there's a rotation in H which moves the first point into the second. (Note that the orbit of a point is a dense set in S2.) We can use the axiom of choice to pick exactly one point from every orbit; collect these points into a set M. Now (almost) every point in S2 can be reached in exactly one way by applying the proper rotation from H to the proper element from M, and because of this, the paradoxical decomposition of H then yields a paradoxical decomposition of S2. The (majority of the) sphere can be divided into four sets (each one dense on the sphere), and when two of these are rotated, we end up with double what we had before.

Step 4. Finally, connect every point on S2 with a ray to the origin; the paradoxical decomposition of S2 then yields a paradoxical decomposition of the solid unit ball minus the center. (The center of the ball needs a bit more care, see below.)

N.B. This sketch glosses over some details. One has to be careful about the set of points on the sphere which happen to lie on the axis of some rotation in H. However, there are only countably many such points, and it is possible to patch them up (see below). The same applies to the center of the ball.

Some details, fleshed out:

In Step 3, we partitioned the sphere into orbits of our group H. To streamline the proof, we omitted the discussion of points that are fixed by some rotation; since the paradoxical decomposition of  relies on shifting certain subsets, the fact that some points are fixed might cause some trouble. Since any rotation of S2 (other than the null rotation) has exactly two fixed points, and since H, which is isomorphic to

relies on shifting certain subsets, the fact that some points are fixed might cause some trouble. Since any rotation of S2 (other than the null rotation) has exactly two fixed points, and since H, which is isomorphic to  , is countable, there are countably many points of S2 that are fixed by some rotation in H, denote this set of fixed points D. Step 3 proves that S2 − D admits a paradoxical decomposition.

, is countable, there are countably many points of S2 that are fixed by some rotation in H, denote this set of fixed points D. Step 3 proves that S2 − D admits a paradoxical decomposition.

What remains to be shown is the Claim: S2 − D is equidecomposable with S2.

Proof. Let λ be some line through the origin that does not intersect any point in D—this is possible since D is countable. Let J be the set of angles, α, such that for some natural number n, and some P in D, r(nα)P is also in D, where r(nα) is a rotation about λ of nα. Then J is countable so there exists an angle θ not in J. Let ρ be the rotation about λ by θ, then ρ acts on S2 with no fixed points in D, i.e., ρn(D) is disjoint from D, and for natural m<n, ρn(D) is disjoint from ρm(D). Let E be the disjoint union of ρn(D) over n = 0,1,2,.... Then S2 = E ∪ (S2 − E) ~ ρ(E) ∪ (S2 − E) = (E − D) ∪ (S2 − E) = S2 − D, where ~ denotes "is equidecomposable to".

For step 4, it has already been shown that the ball minus a point admits a paradoxical decomposition; it remains to be shown that the ball minus a point is equidecomposable with the ball. Consider a circle within the ball, containing the centre of the ball. Using an argument like that used to prove the Claim, one can see that the full circle is equidecomposable with the circle minus the point at the centre of the ball. (Basically, a countable set of points on the circle can be rotated to give itself plus one more point.) Note that this involves the rotation about a point other than the origin, so the Banach-Tarski paradox involves isometries of Euclidean 3-space rather than just SO(3).

We are using the fact that if A ~ B and B ~ C, then A ~ C. The decomposition of A into C can be done using number of pieces equal to the product of the numbers needed for taking A into B and for taking B into C.

The proof sketched above requires 2×4×2 + 8 = 24 pieces, a factor of 2 to remove fixed points, a factor 4 from step 1, a factor 2 to recreate fixed points, and 8 for the center point of the second ball. But in step 1 move {e} and all strings of symbol a only into S(a−1) and do this to all orbits except one. Move {e} of the last orbit to the center of the second ball. This brings the total down to 16 + 1 pieces. With more algebra one can also decompose fixed orbits into 4 sets as in step 1. This gives 5 pieces and is the best possible.

Obtaining infinitely many balls from one

Using the Banach–Tarski paradox, it is possible to obtain k copies of a ball in the Euclidean n-space from one, for any integers n ≥ 3 and k ≥ 1, i.e. a ball can be cut into k pieces so that each of them is equidecomposable to a ball of the same size as the original. Using the fact that the free group  of rank 2 admits a free subgroup of countably infinite rank, a similar proof yields that the unit sphere Sn−1 can be partitioned into countably infinitely many pieces, each of which is equidecomposable (with two pieces) to the Sn−1 using rotations. By using analytic properties of the rotation group SO(n), which is a connected analytic Lie group, one can further prove that the sphere Sn−1 can be partitioned into as many pieces as there are real numbers (that is,

of rank 2 admits a free subgroup of countably infinite rank, a similar proof yields that the unit sphere Sn−1 can be partitioned into countably infinitely many pieces, each of which is equidecomposable (with two pieces) to the Sn−1 using rotations. By using analytic properties of the rotation group SO(n), which is a connected analytic Lie group, one can further prove that the sphere Sn−1 can be partitioned into as many pieces as there are real numbers (that is,  pieces), so that each piece is equidecomposable with two pieces to Sn−1 using rotations. These results then extend to the unit ball deprived of the origin. A recent article of Churkin gives a new proof of the continuous version of the Banach–Tarski paradox.

pieces), so that each piece is equidecomposable with two pieces to Sn−1 using rotations. These results then extend to the unit ball deprived of the origin. A recent article of Churkin gives a new proof of the continuous version of the Banach–Tarski paradox.

The von Neumann paradox in the Euclidean plane

In the Euclidean plane, two figures that are equidecomposable with respect to the group of Euclidean motions are necessarily of the same area, therefore, a paradoxical decomposition of a square or disk of Banach–Tarski type that uses only Euclidean congruences is impossible. A conceptual explanation of the distinction between the planar and higher-dimensional cases was given by John von Neumann: unlike the group SO(3) of rotations in three dimensions, the group E(2) of Euclidean motions of the plane is solvable, which implies the existence of a finitely-additive measure on E(2) and R2 which is invariant under translations and rotations, and rules out paradoxical decompositions of non-negligible sets. Von Neumann then posed the following question: can such a paradoxical decomposition be constructed if one allowed a larger group of equivalences?

It is clear that if one permits similarities, any two squares in the plane become equivalent even without further subdivision. This motivates restricting one's attention to the group SA2 of area-preserving affine transformations. Since the area is preserved, any paradoxical decomposition of a square with respect to this group would be counterintuitive for the same reasons as the Banach–Tarski decomposition of a ball. In fact, the group SA2 contains as a subgroup the special linear group SL(2,R), which in its turn contains the free group F2 with two generators as a subgroup. This makes it plausible that the proof of Banach–Tarski paradox can be imitated in the plane. The main difficulty here lies in the fact that the unit square is not invariant under the action of the linear group SL(2,R), hence one cannot simply transfer a paradoxical decomposition from the group to the square, as in the third step of the above proof of the Banach–Tarski paradox. Moreover, the fixed points of the group present difficulties (for example, the origin is fixed under all linear transformations). This is why von Neumann used the larger group SA2 including the translations, and he constructed a paradoxical decomposition of the unit square with respect to the enlarged group (in 1929). Applying the Banach–Tarski method, the paradox for the square can be strengthened as follows:

- Any two bounded subsets of the Euclidean plane with non-empty interiors are equidecomposable with respect to the area-preserving affine maps.

As von Neumann notes,

- "Infolgedessen gibt es bereits in der Ebene kein nichtnegatives additives Maß (wo das Einheitsquadrat das Maß 1 hat), dass [sic] gegenüber allen Abbildungen von A2 invariant wäre."[6]

- "In accordance with this, already in the plane there is no nonnegative additive measure (for which the unit square has a measure of 1), which is invariant with respect to all transformations belonging to A2 [the group of area-preserving affine transformations]."

To explain this a bit more, the question of whether a finitely additive measure exists, that is preserved under certain transformations, depends on what transformations are allowed. The Banach measure of sets in the plane, which is preserved by translations and rotations, is not preserved by non-isometric transformations even when they do preserve the area of polygons. The points of the plane (other than the origin) can be divided into two dense sets which we may call A and B. If the A points of a given polygon are transformed by a certain area-preserving transformation and the B points by another, both sets can become subsets of the A points in two new polygons. The new polygons have the same area as the old polygon, but the two transformed sets cannot have the same measure as before (since they contain only part of the A points), and therefore there is no measure that "works".

The class of groups isolated by von Neumann in the course of study of Banach–Tarski phenomenon turned out to be very important for many areas of mathematics: these are amenable groups, or groups with an invariant mean, and include all finite and all solvable groups. Generally speaking, paradoxical decompositions arise when the group used for equivalences in the definition of equidecomposability is not amenable.

Recent progress

- Von Neumann's paper left open the possibility of a paradoxical decomposition of the interior of the unit square with respect to the linear group SL(2,R) (Wagon, Question 7.4). In 2000, Miklós Laczkovich proved that such a decomposition exists.[7] More precisely, let A be the family of all bounded subsets of the plane with non-empty interior and at a positive distance from the origin, and B the family of all planar sets with the property that a union of finitely many translates under some elements of SL(2,R) contains a punctured neighbourhood of the origin. Then all sets in the family A are SL(2,R)-equidecomposable, and likewise for the sets in B. It follows that both families consist of paradoxical sets.

- It had been known for a long time that the full plane was paradoxical with respect to SA2, and that the minimal number of pieces would equal four provided that there exists a locally commutative free subgroup of SA2. In 2003 Kenzi Satô constructed such a subgroup, confirming that four pieces suffice.[8]

See also

- Tarski's circle-squaring problem

Notes

- ↑ Michael Potter (2004). Set Theory and Its Philosophy: a Critical Introduction. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0199270414., p. 276.

- ↑ Wilson, Trevor M. (September 2005). "A continuous movement version of the Banach–Tarski paradox: A solution to De Groot's problem". Journal of Symbolic Logic 70 (3): 946–952. doi:10.2178/jsl/1122038921.

- ↑ Banach, Stefan; Tarski, Alfred (1924). "Sur la décomposition des ensembles de points en parties respectivement congruentes" (in French). Fundamenta Mathematicae 6: 244–277. http://matwbn.icm.edu.pl/ksiazki/fm/fm6/fm6127.pdf.

- ↑ M. Foreman and F. Wehrung, The Hahn–Banach theorem implies the existence of a non-Lebesgue measurable set, "Fundamenta Mathematicae" 138 (1991), p. 13-19.

- ↑ Pawlikowski, Janusz: The Hahn–Banach theorem implies the Banach–Tarski paradox. "Fundamenta Mathematicae" 138 (1991), s. 21-22.

- ↑ On p. 85 of J. v. Neumann, "Zur allgemeinen Theorie des Masses", Fundamenta Mathematica 13, p. 73-116, 1929

- ↑ Paradoxical sets under SL2(R), Ann. Univ. Sci. Budapest. Eötvös Sect. Math. 42 (1999), 141–145.

- ↑ A locally commutative free group acting on the plane, Fundamenta Mathematica, 180 (2003), no. 1, 25–34.

References

- Banach, Stefan; Tarski, Alfred (1924). "Sur la décomposition des ensembles de points en parties respectivement congruentes" (PDF). Fundamenta Mathematicae 6: 244–277. http://matwbn.icm.edu.pl/ksiazki/fm/fm6/fm6127.pdf.

- Churkin, V. A. (2010). "A continuous version of the Hausdorff–Banach–Tarski paradox". Algebra and Logic 49 (1): 91–98. doi:10.1007/s10469-010-9080-y.

- Kuro5hin. "Layman's Guide to the Banach–Tarski Paradox". http://www.kuro5hin.org/story/2003/5/23/134430/275.

- Stromberg, Karl (March 1979). "The Banach–Tarski paradox". The American Mathematical Monthly (Mathematical Association of America) 86 (3): 151–161. doi:10.2307/2321514. http://jstor.org/stable/2321514.

- Su, Francis E.. "The Banach–Tarski Paradox" (PDF). http://www.math.hmc.edu/~su/papers.dir/banachtarski.pdf.

- von Neumann, John (1929). "Zur allgemeinen Theorie des Masses" (PDF). Fundamenta Mathematicae 13: 73–116. http://matwbn.icm.edu.pl/ksiazki/fm/fm13/fm1316.pdf.

- Wagon, Stan (1994). The Banach–Tarski Paradox. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45704-1. http://gen.lib.rus.ec/get?md5=d18da4c7b2a7109e31d63f28df55dbc1.

- Wapner, Leonard M. (2005). The Pea and the Sun: A Mathematical Paradox. Wellesley, Mass.: A.K. Peters. ISBN 1-56881-213-2. http://gen.lib.rus.ec/get?md5=59f223482492f1644b1023fccd4968f1.

External links

- The Banach-Tarski Paradox by Stan Wagon (Macalester College), the Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Irregular Webcomic! #2339 by David Morgan-Mar provides a non-technical explanation of the paradox. It includes a step-by-step demonstration of how to create two spheres from one.